Infection Fighters

The ears, nose and throat are point of entry into the body and need to be well protected against invading micro-organisms. In preventing bacteria and viruses from travelling further afield, they sometimes become the focus of infection themselves, so these areas have rich blood supplies, which can transport large numbers of white blood cells to the area when needed.

The Ears

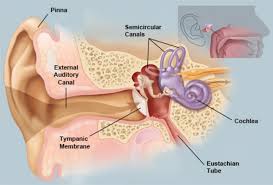

The ears' external structure channels sound waves along the ear canal to the eardrum. In response, the eardrum vibrates and the vibrations pass through the air-filled space of the middle ear along three tiny bones, collectively called the ossicles.

These bones carry vibrations to the oval window and thence into the cochlea, a part of the inner ear. Here they stimulate tiny hair cells to produce electrical nerve signals.

These nerve signals are transmitted to the brain where they are decoded into decoded into recognisable sounds. The ears are also involved in our sense of balance. Three liquid filled canals within the inner ear help the brain to determine the position of the head and whether the body is stationary or rotating. This information is processed in the brain, along with visual stimuli and messages from the limbs, allowing you to maintain a sensation of balance despite postural changes.

Ears can be prone to infection via the eustachian tubes, canals which link the middle ear to the throat. Their role is to maintain equal air pressure on either side of the eardrum, but they act as a passage for micro-organisms from the throat to the ear or vice versa. Middle ear infections are common in children. Inner ear infections can cause dizziness, vertigo and nausea.

The Nose

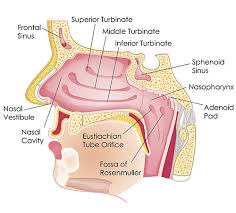

The nose is the organ of smell. Tiny hairs, called olfactory cilia, on nerve cells high up in the nose, are sensitive to aromatic molecules, and transmit nerve messages to the brain. Unlike messages from other sense organs, aromatic messages enter the limbic system. This region deals with powerful emotions and buried memories, which could explain why the sense of smell can evoke such strong responses. Certain aromas may also stimulate the release of specific neurotransmitters. Eventually, the messages are decoded in the temporal part of the brain and we recognise smell.

As well as enabling us to smell the nose is an organ of respiration. We are designed to inhale air mainly through our nose, rather than our mouth, for several reasons. Firstly, the nose has an excellent blood supply, and air passing through is warmed by its lining.

It is also moistened by the mucus produced by special goblet cells. This warm, moist air is good for the lungs. The mucus membrane that lines the nose also has tiny hairs or cilia on its surface and these wave like seaweed underwater. They catch particles of dirt and micro-organisms and trap them in the mucus. The cilia then waft them either out of the nose or to the throat to be coughed away. This is an important defence against infection of the lower respiratory passages.

When we contract an infection or come into contact with an allergen, such as pollen, our mucus membranes are stimulated to produce increased amounts of mucus to wash the particles away. Hence the sneezes and runny nose of hay fever.

A complication of nasal infection can be sinusitis. Sinuses are air spaces inside the large facial bones which help to reduce their weight. Like the nose, they are lined with mucous membrane. When this becomes inflamed or infected, the increased mucus cannot escape easily as the drainage canals from the sinuses to the nasal cavities are narrow. The accumulation of mucus can lead to intense feelings of pressure and severe headaches or facial pain around the eyes and even the teeth. Sinusitis can become chronic, recurring even when there is no respiratory infection.

The Throat

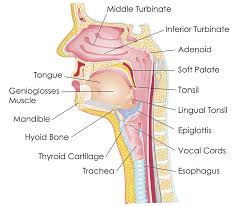

The throat is accessible to the outside world via the mouth, the nostrils and the two eustachian tubes, so it's hardly surprising that infections can often start here. A sore throat can be the first sign that micro-organisms have taken up residence and are multiplying before they travel further into the respiratory system.

As that process can take several hours or days, the immune system has the chance to fight back. If this is successful, the sore throat will come and go within a couple of days. If it's unsuccessful, a throat infection, bronchitis, or a generalised infection, such as flu, may develop.

There are two sets of lymphatic structure in this area. The adenoids - at the back of the upper throat/nose, near the eustachian tubes, and the tonsils - a little lower down. They all help to defend against inhaled or swallowed micro-organisms, and are particularly active during childhood. In some children, the adenoids become enlarged, causing breathing difficulties. Tonsils can become infected or ulcerated, causing very painful throats. In severe cases they may have to be removed.