What happens to the food we eat?

The role of the digestive system is to convert the complex food we eat into simple forms that can be absorbed into our bodies and used for energy, growth, repair and the manufacture of essential chemicals. It does this by physically breaking food into smaller pieces, and also by chemically digesting it into simpler molecules using the enzymes in our digestive juices.

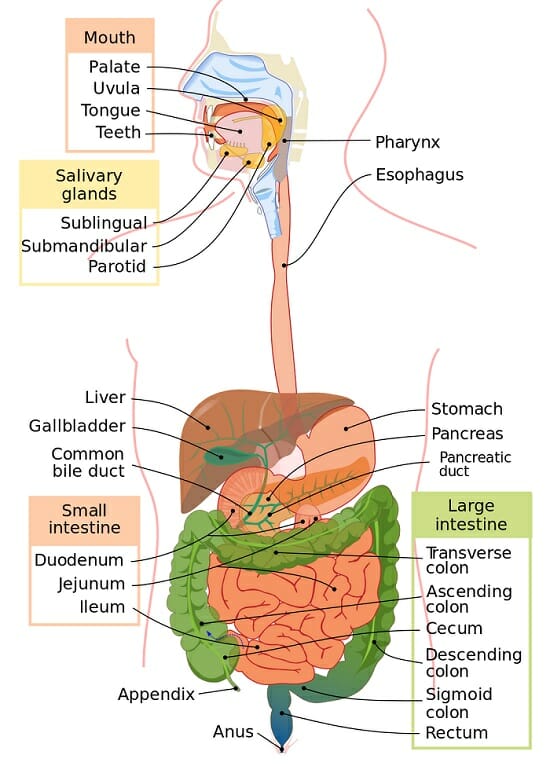

Most of the digestive system is a long, coiled tube through which food passes. This tube is known as the alimentary tract, and it runs from the mouth to the anus. In some places such as the stomach, there tube is quite wide, while in others, the small intestine for example, it is only about 2.5cm in diameter. Other organs open into this tube, pouring chemicals onto the food to break it down.

Each part of the alimentary tract has its own specific structure and functions. In the mouth, food is crushed by teeth, mixed with the first digestive juice, saliva, moulded into a ball or 'bolus' by the tongue, and then swallowed. Saliva begins the breakdown of starches into simpler sugars. Once in the oesophagus, the bolus is propelled into the stomach by a wave of muscular contraction known as peristalsis.

In the stomach, food is mixed with the next digestive juice, highly acidic gastric juice. Gastric juice contains enzymes and hydrochloric acid, and its main function is to begin the breakdown of proteins. Gastric juice is strong enough to break down our own stomach lining, so we have glands that produce a layer of mucous to protect it. Food is held in the stomach for two to four hours, allowing time for the gastric juice and peristalsis to reduce it to a semi-liquid form. Peristalsis in the stomach produces as strong churning action which ensures the contents are thoroughly mixed.

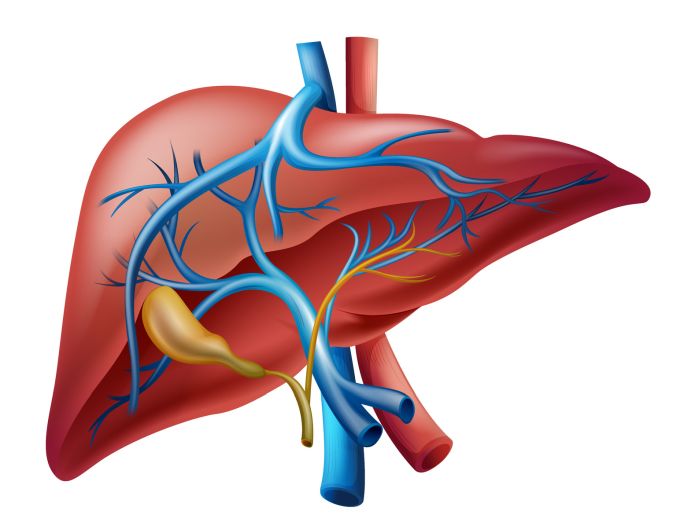

The food mass is released from the stomach in small quantities and passes into the first part of the small intestine - the duodenum. The small intestine is a muscular tube approximately 7m in length. It's called the small intestine because of its narrow diameter. The duodenum is about 30cm in length and halfway along there is an opening where digestive juices from the gall bladder and pancreas pour in to mix with the food. When fat is detected in food, the gall bladder releases a chemical called bile which emulsifies the fat into smaller droplets. The pancreas manufactures and releases pancreatic juice - a mix of enzymes that continues the breakdown of starches, proteins and fats.

As the food passes further down the small intestine, into the part known as the jejunum, intestinal juice containing enzymes completes the breakdown of fats, sugars and proteins. In the next region of the small intestine - the ileum - these molecules are absorbed into the bloodstream through tiny, finger like structures called villi, which line the walls.

It takes about eight hours for the food to travel from the mouth to this point. However, before the absorbed nutrients can be used by the body, they are carried to the liver - our main chemical processing organ. Here they can be recombined to make new substances, stored, or released back into the bloodstream for the cells of the body to use.

Any remaining material in the small intestine then passes into the large intestine - a wider, muscular tube roughly twice the diameter of its smaller namesake. What remains, after the nutrients have been absorbed, is a semi-solid mass of indigestible fibre (mainly from plant sources), waste digestive enzymes and cells sloughed off the inner walls of the digestive organs. This material is further digested by colonies of bacteria living in the intestine, known as gut flora. The remaining water is excreted as faeces. As peristalsis is much slower in the large intestine, this process can take up to a further 12 hours.

Stress and the Digestive System

Of all the body's systems, the digestive system seems to be most directly affected by stress. This is because the process of digestion uses a great deal of energy, and the digestive organs require a large blood supply to work efficiently. Our body's response to stress is to redirect blood to the heart, lungs and muscles for fight or flight. If a state of stress is maintained over extended periods the rhythm of peristalsis and the production of digestive enzymes can be disrupted and digestive problems can occur.

Recently, gastritis - inflammation of the stomach - the oesophagus - irritation of the lower oesophagus - have become more common. In both these conditions, it is the body's own acidic stomach contents that cause the damage, leading to intense, burning pain. The over-acidity is often triggered by stress and made worse by, for example, excessive use of alcohol, caffeine, certain painkillers and smoking. There is an associated risk of stomach ulcers.

Perhaps the most common digestive disorder is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). One in four woman and one in ten men suffer from this at some time. Woman may be more vulnerable as their monthly hormonal cycle already has a pronounced effect on bowel activity. Symptoms include nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, bloating, flatulence and griping pain. Stress and anxiety, irregular eating habits and food intolerance are all possible causes.

Gallstones are small calcified granules which accumulate in the gall bladder and can cause pain when the gall bladder contracts to squeeze bile into the duodenum. They are also associated with high-fat diets.