Anatomy of the Neck and Shoulders

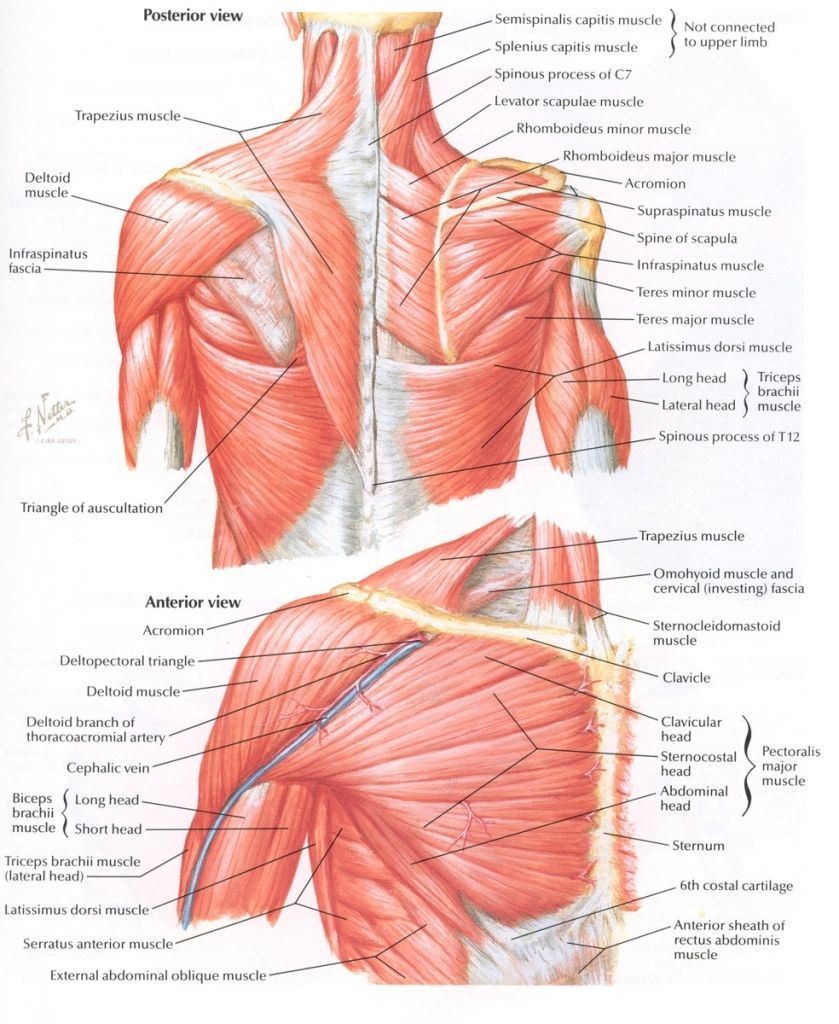

The neck is one of the most flexible parts of the spine, able to bend to the front and side, and, to a lesser extent, backwards, and allowing a large degree of rotation. Many muscles are needed to engineer all these movements. They range from large sheets of muscles, such as the two trapezius muscles, which cover the upper back and shoulders in a kite shape, to the thick, rope-like sternocleidomastoids, running diagonally down either side of the throat. The head is a heavy weight for the neck to support, and many smaller muscles work together to keep it balanced. Because of this close relationship between the head and neck it is common for tension in the neck muscles to affect the scalp muscles leading to tension headaches.

The shoulder is a ball and socket joint which allows a very wide range of movement. The ball-like end of the upper arm bone is held in a socket formed by part of the shoulder blade and collar bone, together with ligaments and tendons. The shoulder is more flexible than the hip, the body's other ball and socket joint, but also more vulnerable to injury. The reason for this is the difference in construction of the two. The shoulder socket is shallower than its hip counterpart, and relies on muscles, tendons and ligaments, to hold the arm in place, rather than having it kept in place by bones. These softer tissues are more likely to be strained or damaged by over-use, poor posture, or sudden, vigorous exercise.

Name that Muscle

Some of the main muscles of the neck and shoulders are:

- Latissimus dorsi which helps to pull the arms back and down, as in rowing.

- Pectorals which work in the opposite way to bring the arms forward.

- Levator scapulae which stabilise the shoulder blades during other movements.

- Sternocleidomastoid which turns the head and pulls it forward.

If one or more of these muscles is strained, you may suffer from headaches, a still neck, frozen shoulder, or even a trapped nerve. This could show itself in pins and needles or discomfort travelling beyond the injured neck and shoulder region. If movement is restricted, circulation will tend to suffer, resulting in a build-up of muscle wastes in the area. This then causes further stiffness and lack of movement, a vicious cycle.

Stress and the Neck and Shoulders

Of all the parts of the body, the neck and shoulders are the most commonly affected by the physical signs of stress. When we are fearful or anxious, our body produces the chemical adrenaline in much higher levels than usual. One purpose of adrenaline is to prepare the muscles, when we are faced with 'danger', for fight or flight, to the neck and shoulders become tensed an tightened, ready to respond in a instant.

However, most of our modern day problems are not easily solved by fighting or running away, much as we might wish to do either of those things. As a result, the muscle tension is not allowed a natural release, so the brain thinks we are still under threat and reinforces the message to the muscles, which remain in their state of semi-readiness for much longer than they were designed to. We then go on to experience something similar to the stiffness and discomfort caused by excessive exercise, due to the build-up of muscle wastes.

If the fight or flight response is repeated often enough, the body's sense of being on red alert will impact on the circulation, which may become impaired, muscle stiffness increases and the joints of the neck and shoulders can lose mobility. This tends to happen over time and, unless we use the full range of movements in these joints regularly, it may come as a sudden and unpleasant surprise to find that we can't look over our shoulder to check that tricky reverse parking manoeuvre.

Learning to let go

Because the neck and shoulder area is so susceptible to the effects of mental as well as physical stress, we can use techniques that work either through the mind or the body to relieve discomfort. If tension in the body is eased through stretching exercises, massage or other types of hands- on manipulations, the brain may respond to the physical relaxation by calling off the state of alert.

Alternatively, forms of mental relaxation such as meditation, can soothe brain activity, calming the fight or flight response and allowing the muscles to revert to their normal relaxed condition. Even better is a combination of the two approaches. An aromatic bath, for example, combines mental and physical relaxation to soothe neck and shoulder tension. The heat of the water improves circulation and increases penetration of essential oils that can have powerful relaxing and anti-depressant effects.

Inhaling a favourite aroma associated with feelings of calm and relaxation helps recapture those emotions in stressful situations. Although this doesn't directly affect the muscles, by calming the mind it can help prevent the stress response that causes them to become tense.

Ways to use essential oils

Aromatherapy can be extremely effective for muscles affected by stress. The combination of essential oils with massage works on both the physical and mental state. Physically, the oils may be antispasmodic (helping relax the muscles), analgesic (pain-relieving), or can improve circulation (helping to remove build-up of muscle wastes and supply fresh nutrients). Mentally the inhalation of essential oils can help bring about a feeling of tranquillity.